In many applications a matrix has less than full rank, that is,

. Sometimes,

is known, and a full-rank factorization

with

and

, both of rank

, is given—especially when

or

. Often, though, the rank

is not known. Moreover, rather than being of exact rank

,

is merely close to a rank

matrix because of errors from various possible sources.

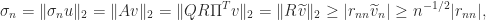

What is usually wanted is a factorization that displays how close is to having particular ranks and provides an approximation to the range space of a lower rank matrix. The ultimate tool for providing this information is the singular value decomposition (SVD)

where ,

, and

and

are orthogonal. The Eckart–Young theorem says that

and that the minimum is attained at

so is the best rank-

approximation to

in both the

-norm and the Frobenius norm.

Although the SVD is expensive to compute, it may not be significantly more expensive than alternative factorizations. However, the SVD is expensive to update when a row or column is added to or removed from the matrix, as happens repeatedly in signal processing applications.

Many different definitions of a rank-revealing factorization have been given, and they usually depend on a particular matrix factorization. We will use the following general definition.

Definition 1. A rank-revealing factorization (RRF) of

is a factorization

where

,

is diagonal and nonsingular, and

and

are well conditioned.

An RRF concentrates the rank deficiency and ill condition of into the diagonal matrix

. An RRF clearly exists, because the SVD is one, with

and

having orthonormal columns and hence being perfectly conditioned. Justification for this definition comes from a version of Ostrowski’s theorem, which shows that

where . Hence as long as

and

are well conditioned, the singular values are good order of magnitude approximations to those of

up a scale factor.

Without loss of generality we can assume that

(since for any permutation matrix

and the second expression is another RRF). For

we have

so is within distance of order

from the rank-

matrix

, which is the same order as the distance to the nearest rank-

matrix if

.

Definition 2 is a strong requirement, since it requires all the singular values of to be well approximated by the (scaled) diagonal elements of

. We will investigate below how it compares with another definition of RRF.

Numerical Rank

An RRF helps to determine the numerical rank, which we now define.

Definition 2. For a given

the numerical rank of

is the largest integer

such that

.

By the Eckart–Young theorem, the numerical rank is the smallest rank attained over all with

. For the numerical rank to be meaningful in the sense that it is unchanged if

is perturbed slightly, we need

not to be too close to

or

, which means that there must be a significant gap between these two singular values.

QR Factorization

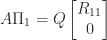

One might attempt to compute an RRF by using a QR factorization , where

has orthonormal columns,

is upper triangular, and we assume that

. In Definition 1, we can take

However, it is easy to see that QR factorization in its basic form is flawed as a means for computing an RRF. Consider the matrix

which is a Jordan block with zero eigenvalue. This matrix is its own QR factorization (), and the prescription

gives

, so

. The essential problem is that the diagonal of

has no connection with the nonzero singular values of

. What is needed are column permutations:

for the permutation matrix

that reorders

to

, and this is a perfect RRF with

.

For a less trivial example, consider the matrix

Computing the QR factorization we obtain

R =

-2.0000e+00 5.0000e-01 -2.5000e+00 5.0000e-01

0 1.6583e+00 -1.6583e+00 -1.5076e-01

0 0 -4.2640e-09 8.5280e-01

0 0 0 -1.4142e+00

The element tells us that

is within distance about

of being rank deficient and so has a singular value bounded above by this quantity, but it does not provide any information about the next larger singular value. Moreover, in

,

is of order

for this factorization. We need any small diagonal elements to be in the bottom right-hand corner, and to achieve this we need to introduce column permutations to move the “dependent columns” to the end.

QR Factorization With Column Pivoting

A common method for computing an RRF is QR factorization with column pivoting, which for a matrix with

computes a factorization

, where

is a permutation matrix,

has orthonormal columns, and

is upper triangular and satisfies the inequalities

In particular,

If with

then we can write

with

Hence is within

-norm distance

of the rank-

matrix

. Note that if

is partitioned conformally with

in (4) then

so , which means that

provides an

approximation to the range of

.

To assess how good an RRF this factorization is (with ) we write it as

Applying (1) gives

where , since

has orthonormal columns and so has unit singular values. Now

has unit diagonal and, in view of (2), its off-diagonal elements are bounded by

. Therefore

. On the other hand,

by Theorem 1 in Bounds for the Norm of the Inverse of a Triangular Matrix. Therefore

The lower bound is an approximate equality for small for the triangular matrix

devised by Kahan, which is invariant under QR factorization with column pivoting. Therefore QR factorization with column pivoting is not guaranteed to reveal the rank, and indeed it can fail to do so by an exponentially large factor.

For the matrix , QR with column pivoting reorders

to

and yields

R =

-3.0000e+00 3.3333e-01 1.3333e+00 -1.6667e+00

0 -1.6997e+00 2.6149e-01 2.6149e-01

0 0 1.0742e+00 1.0742e+00

0 0 0 3.6515e-09

This suggests a numerical rank of

for

(say). In fact, this factorization provides a very good RRF, as in

we have

.

QR Factorization with Other Pivoting Choices

Consider a factorization

with triangular factor partitioned as

We have

where (7) is from singular value interlacing inequalities and (8) follows from the Eckart-Young theorem, since setting to zero gives a rank-

matrix. Suppose

has numerical rank

and

. We would like to be able to detect this situation from

, so clearly we need

In view of the inequalities (7) and (8) this means that we wish to choose maximize

and minimize

.

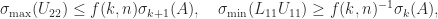

Some theoretical results are available on the existence of such QR factorizations. First, we give a result that shows that for the approximations in (9) can hold to within a factor

.

Theorem 1. For

with

there exists a permutation

such that

has the QR factorization

with

and

, where

.

Proof. Let

, with

and let

be such that

satisfies

. Then if

is a QR factorization,

since

, which yields the result.

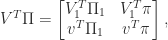

Next, we write

, where

, and partition

with

. Then

implies

. On the other hand, if

is an SVD with

,

, and

then

so

Finally, we note that we can partition the orthogonal matrix

as

and the CS decomposition implies that

Hence

, as required.

Theorem 1 is a special case of the next result of Hong and Pan (1992).

Theorem 2. For

with

and any

there exists a permutation matrix

such that

has the QR factorization

where, with

partitioned as in (6),

where

.

The proof of Theorem 2 is constructive and chooses to move a submatrix of maximal determinant of

to the bottom of

, where

comprises the last

columns of the matrix of right singular vectors.

Theorem 2 shows the existence of an RRF up to the factor , but it does not provide an efficient algorithm for computing one.

Much work has been done on algorithms that choose the permutation matrix in a different way to column pivoting or post-process a QR factorization with column pivoting, with the aim of satisfying (9) at reasonable cost. Typically, these algorithms involve estimating singular values and singular vectors. We are not aware of any algorithm that is guaranteed to satisfy (9) and requires only

flops.

UTV Decomposition

By applying Householder transformations on the right, a QR factorization with column pivoting can be turned into a complete orthogonal decomposition of , which has the form

where is upper triangular and

and

are orthogonal. Stewart (1998) calls (6) with

upper triangular or lower triangular a UTV decomposition and he defines a rank-revealing UTV decomposition of numerical rank

by

The UTV decomposition is easy to update (when a row is added) and downdate (when a row is removed) using Givens rotations and it is suitable for parallel implementation. Initial determination of the UTV decomposition can be done by applying the updating algorithm as the rows are brought in one at a time.

LU Factorization

Instead of QR factorization we can build an RRF from an LU factorization with pivoting. For with

, let

where and

are permutation matrices,

and

are

lower and

upper triangular, respectively, and

and

are

. Analogously to (7) and (8), we always have

and

. With a suitable pivoting strategy we can hope that

and

.

A result of Pan (2000) shows that an RRF based on LU factorization always exists up to a modest factor . This is analogue for LU factorization of Theorem 2.

Theorem 3 For

with

and any

there exist permutation matrices

and

such that

![\notag \Pi_1 A \Pi_2 = LU = \begin{bmatrix} L_{11} & 0 \\ L_{12} & I_{m-k,n-k} \end{bmatrix} \begin{array}[b]{@{\mskip33mu}c@{\mskip-16mu}c@{\mskip-10mu}c@{}} \scriptstyle k & \scriptstyle n-k & \\ \multicolumn{2}{c}{ \left[\begin{array}{c@{~}c@{~}} U_{11}& U_{12} \\ 0 & U_{22} \\ \end{array}\right]} & \mskip-12mu\ \begin{array}{c} \scriptstyle k \\ \scriptstyle n-k \end{array} \end{array},](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cnotag+++++%5CPi_1+A+%5CPi_2+%3D+LU+%3D+++++%5Cbegin%7Bbmatrix%7D+++++L_%7B11%7D+%26++0++++%5C%5C+++++L_%7B12%7D+%26+I_%7Bm-k%2Cn-k%7D+++++%5Cend%7Bbmatrix%7D++++%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%5Bb%5D%7B%40%7B%5Cmskip33mu%7Dc%40%7B%5Cmskip-16mu%7Dc%40%7B%5Cmskip-10mu%7Dc%40%7B%7D%7D++++%5Cscriptstyle+k+%26++++%5Cscriptstyle+n-k+%26++++%5C%5C++++%5Cmulticolumn%7B2%7D%7Bc%7D%7B++++++++%5Cleft%5B%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bc%40%7B%7E%7Dc%40%7B%7E%7D%7D++++++++++++++++++U_%7B11%7D%26+U_%7B12%7D+%5C%5C++++++++++++++++++++0+++%26+U_%7B22%7D+%5C%5C++++++++++++++%5Cend%7Barray%7D%5Cright%5D%7D++++%26+%5Cmskip-12mu%5C++++++++++%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bc%7D++++++++++++++%5Cscriptstyle+k+%5C%5C++++++++++++++%5Cscriptstyle+n-k++++++++++++++%5Cend%7Barray%7D++++%5Cend%7Barray%7D%2C+&bg=ffffff&fg=222222&s=0&c=20201002)

where

is unit lower triangular,

is upper triangular, and

where

.

Again the proof is constructive, but the permutations it chooses are too expensive to compute. In practice, complete pivoting often yields a good RRF.

In terms of Definition 1, an RRF has

For the matrix (), the

factor for LU factorization without pivoting is

U =

1.0000e+00 1.0000e+00 1.0000e-08 0

0 -2.0000e+00 2.0000e+00 1.0000e+00

0 0 5.0000e-09 -1.5000e+00

0 0 0 -2.0000e+00

As for QR factorization without pivoting, an RRF is not obtained from .. However, with complete pivoting we obtain

U =

2.0000e+00 1.0000e+00 -1.0000e+00 1.0000e+00

0 -2.0000e+00 0 0

0 0 1.0000e+00 1.0000e+00

0 0 0 -5.0000e-09

which yields a very good RRF with

and

.

Notes

QR factorization with column pivoting is difficult to implement efficiently, as the criterion for choosing the pivots requires the norms of the active parts of the remaining columns and this requires a significant amount of data movement. In recent years, randomized RRF algorithms have been developed that use projections with random matrices to make pivot decisions based on small sample matrices and thereby reduce the amount of data movement. See, for example, Martinsson et al. (2019).

References

This is a minimal set of references, which contain further useful references within.

- Shivkumar Chandrasekaran and Ilse C. F. Ipsen, On Rank-Revealing Factorisations, SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 15 (2), 592–622, 1994

- Y. P. Hong and C.-T. Pan, Rank-Revealing QR Factorizations and the Singular Value Decomposition, Math. Comp. 58 (197), 213–232, 1992.

- P. G. Martinsson, G. Quintana-Orti, and N. Heavner, randUTV: A Blocked Randomized Algorithm for Computing a Rank-Revealing UTV Factorization, ACM Trans. Math. Software 45(1), 4:1–4:26, 2019.

- C.-T. Pan, On the Existence and Computation of Rank-Revealing LU Factorizations, Linear Algebra Appl. 316, 199–222, 2000.

- G. W. Stewart, Matrix Algorithms. Volume I: Basic Decompositions, Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1998.

Related Blog Posts

- What Is the CS Decomposition? (2020)

- What Is an LU Factorization? (2021)

- What Is a QR Factorization? (2020)

- What Is the Singular Value Decomposition? (2020)

This article is part of the “What Is” series, available from https://nhigham.com/category/what-is and in PDF form from the GitHub repository https://github.com/higham/what-is.