In finite precision arithmetic the result of an elementary arithmetic operation does not generally lie in the underlying number system, , so it must be mapped back into

by the process called rounding. The most common choice is round to nearest, whereby the nearest number in

to the given number is chosen; this is the default in IEEE standard floating-point arithmetic.

Round to nearest is deterministic: given the same number it always produces the same result. A form of rounding that randomly rounds to the next larger or next smaller number was proposed Barnes, Cooke-Yarborough, and Thomas (1951), Forysthe (1959), and Hull and Swenson (1966). Now called stochastic rounding, it comes in two forms. The first form rounds up or down with equal probability .

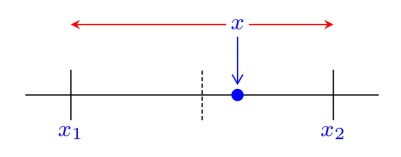

We focus here on the second form of stochastic rounding, which is more interesting. To describe it we let be the given number and let

and

with

be the adjacent numbers in

that are the candidates for the result of rounding. The following diagram shows the situation where

lies just beyond the half-way point between

and

:

We round up to with probability

and down to

with probability

; note that these probabilities sum to

. The probability of rounding to

and

is proportional to one minus the relative distance from

to each number.

If stochastic rounding chooses to round to in the diagram then it has committed a larger error than round to nearest, which rounds to

. Indeed if we focus on floating-point arithmetic then the result of the rounding is

where is the unit roundoff. For round to nearest the same result is true with the smaller bound

. In addition, certain results that hold for round to nearest, such as

and

, can fail for stochastic rounding. What, then, is the benefit of stochastic rounding?

It is not hard to show that the expected value of the result of stochastically rounding is

itself (this is obvious if

, for example), so the expected error is zero. Hence stochastic rounding maintains, in a statistical sense, some of the information that is discarded by a deterministic rounding scheme. This property leads to some important benefits, as we now explain.

In certain situations, round to nearest produces correlated rounding errors that cause systematic error growth. This can happen when we form the inner product of two long vectors and

of nonnegative elements. If the elements all lie on

then clearly the partial sum can grow monotonically as more and more terms are accumulated until at some point all the remaining terms “drop off the end” of the computed sum and do not change it—the sum stagnates. This phenomenon was observed and analyzed by Huskey and Hartree as long ago as 1949 in solving differential equations on the ENIAC. Stochastic rounding avoids stagnation by rounding up rather than down some of the time. The next figure gives an example. Here,

and

are

-vectors sampled from the uniform

distribution, the inner product is computed in IEEE standard half precision floating-point arithmetic (

), and the backward errors are plotted for increasing

. From about

, the errors for stochastic rounding (SR, in orange) are smaller than those for round to nearest (RTN, in blue), the latter quickly reaching 1.

The figure is explained by recent results of Connolly, Higham, and Mary (2020). The key property is that the rounding errors generated by stochastic rounding are mean independent (a weaker version of independence). As a consequence, an error bound proportional to can be shown to hold with high probability. With round to nearest we have only the usual worst-case error bound, which is proportional to

. In the figure above, the solid black line is the standard backward error bound

while the dashed black line is

. In this example the error with round to nearest is not bounded by a multiple of

, as the blue curve crosses the dashed black one. The underlying reason is that the rounding errors for round to nearest are correlated (they are all negative beyond a certain point in the sum), whereas those for stochastic rounding are uncorrelated.

Another notable property of stochastic rounding is that the expected value of the computed inner product is equal to the exact inner product. The same is true more generally for matrix–vector and matrix–matrix products and the solution of triangular systems.

Stochastic rounding is proving popular in neural network training and inference when low precision arithmetic is used, because it avoids stagnation.

Implementing stochastic rounding efficiently is not straightforward, as the definition involves both a random number and an accurate value of the result that we are trying to compute. Possibilities include modifying low level arithmetic routines (Hopkins et al., 2020) and exploiting the augmented operations in the latest version of the IEEE standard floating-point arithmetic (Fasi and Mikaitis, 2020).

Hardware is starting to become available that supports stochastic rounding, including the Intel Lohi neuromorphic chip, the Graphcore Intelligence Processing Unit (intended to accelerate machine learning), and the SpiNNaker2 chip.

Stochastic rounding can be done in MATLAB using the chop function written by me and Srikara Pranesh. This function is intended for experimentation rather than efficient computation.

References

This is a minimal set of references, which contain further useful references within.

- R. C. M. Barnes, E. H. Cooke-Yarborough, and D. G. A. Thomas, An electronic digital computor using cold cathode counting tubes for storage, Electronic Eng. 23, 286–291, 1951.

- Michael P. Connolly, Nicholas J. Higham and Theo Mary, Stochastic Rounding and Its Probabilistic Backward Error Analysis, MIMS EPrint 2020.12, The University of Manchester, UK, April 2020.

- Massimiliano Fasi and Mantas Mikaitis, Algorithms for Stochastically Rounded Elementary Arithmetic Operations in IEEE 754 Floating-Point Arithmetic, MIMS EPrint 2020.9, The University of Manchester, UK, February 2020.

- George Forsythe, Reprint of a note on rounding-off errors, SIAM Rev. 1(1), 66–67, 1959.

- Suyog Gupta and Ankur Agrawal and Kailash Gopalakrishnan and Pritish Narayanan, Deep Learning with Limited Numerical Precision, in Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning – Volume 37, ICML’15, JMLR.org, 2015, pp. 1737–1746,

- Michael Hopkins, Mantas Mikaitis, Dave Lester, and Steve Furber, Stochastic rounding and reduced-precision fixed-point arithmetic for solving neural ordinary differential equations, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 378 (2166), 1–22, 2020.

- T. E. Hull and J. R. Swenson, Tests of probabilistic models for propagation of roundoff errors, Comm. ACM 9 (3), 108–113, 1966.

Related Blog Posts

- Stochastic Rounding Has Unconditional Probabilistic Error Bounds by Michael P. Connolly (2020)

- What Is Floating-Point Arithmetic? (2020)

- What Is IEEE Standard Arithmetic? (2020)

- What Is Rounding? (2020)

This article is part of the “What Is” series, available from https://nhigham.com/category/what-is and in PDF form from the GitHub repository https://github.com/higham/what-is.