In 1981 my mother showed me a magazine (Woman’s Realm) that had instructions for producing on a typewriter a portrait of Prince Charles. The instructions had been designed by Bob Neill, who had worked out how represent a photograph of Prince Charles as a 100-by-79 grid of characters, choosing the density of each character appropriately and exploiting the facility of a typewriter to issue a carriage return without line feed and thereby overwrite one character with another. The instructions looked like

(6) 26G 16@ 1& 36G

(6a) 22sp 2. 1: 95 1& 15 1& 3S 2& 3: 1.

which say that on the 6th line you should type the letter G 26 times followed by 16 @ symbols, etc., then overwrite the line with 22 spaces, 2 full stops, etc.

This is an example of ASCII art, though ASCII art does not usually involve overwriting characters.

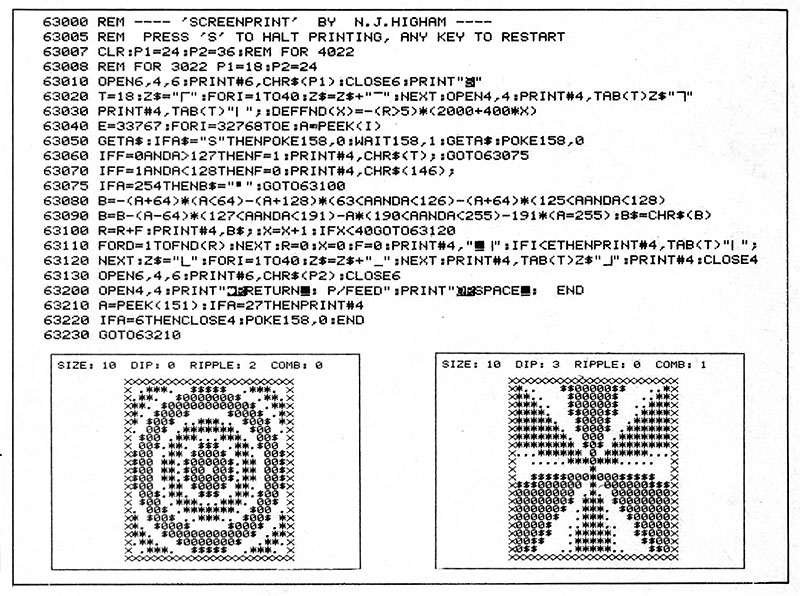

At the time I had a Commodore Pet microcomputer and it struck me that the painstaking process of typing the image would be better turned into a computer program. Once written and debugged the program could be used to print multiple copies of the image. By switching the data set the program could be used to print other photos. So I wrote a program in Commodore Basic that printed the image to a Commodore 4022 dot matrix printer.

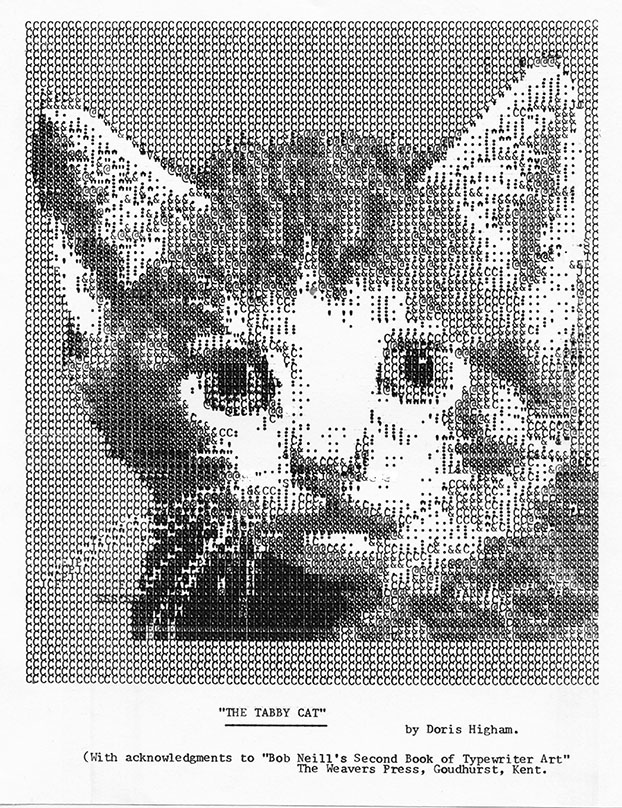

I sent the program to Bob. He liked it and printed the program in an appendix to his 1982 book Bob Neill’s Book of Typewriter Art (With Special Computer Programme). That book contains instructions for typing 20 different images, including other members of the royal family, Elvis Presley and Telly Savalas (the actor who played Kojak in the TV series of the same name, which was popular at the time), and various animals,. Bob Neill’s Second Book of Typewriter Art was published in 1984, which reprinted my original program. It included further celebrities such as Adam Ant, Benny from Crossroads, “J.R.” from Dallas and Barry Manilow

I recently came across some articles describing Bob’s work, including one by his daughter, Barbara, one by Lori Emerson that includes a PDF scan of the first book, and an article The Lost Ancestors of ASCII Art. The latter pointed me to a recently published book Typewriter Art: A Modern Anthology. This resurgence of interest in typewriter art prompted me to look again at my code.

I had revisited my original 1982 Basic code later in the 1980s, converting it to GW-Basic so it would run on IBM PCs with Epson printers. I had also added the data for The Tabby Cat from Bob’s second book. Here is an extract from the code, complete with GOTOs and GOSUBs (GW-Basic had few structured programming features).

10 REM TYPEART.BAS

20 REM Program by Nick Higham 1982 (Commodore Basic),

30 REM and 1988 (GW-Basic/Turbo Basic). (c) N.J. Higham 1982, 1988.

40 REM Designs by Bob Neill. (c) A.R. Neill 1982, 1984.

...

530 REM -----------------------------

540 REM ROUTINE TO PRINT OUT DATABASE

550 REM -----------------------------

560 DEV$ = "LPT"+PP$+":"

570 OPEN DEV$ FOR OUTPUT AS #1

580 PRINT #1, RESET.CODE$

590 WIDTH #1,255 ' this stops basic inserting unwanted carriage returns

600 GOSUB 800

610 L$=""

620 GOSUB 700:IF A$="/" THEN PRINT#1, NORMAL.LFEED$+L$: GOTO 610

630 IF A$="-" THEN PRINT#1, ZERO.LFEED$;L$: GOTO 610

640 A=ASC(A$):IF A>47 AND A<58 THEN A=A-48: GOTO 660

650 L$=L$+A$: GOTO 620

660 GOSUB 700:B=ASC(A$):IF B>47 AND B<58 THEN A=10*A+B-48: GOSUB 700

670 FOR I=1 TO A:L$=L$+A$:NEXT: GOTO 620

680 '

690 REM -- SUBROUTINE TO TAKE NEXT CHARACTER FROM Z$

700 A$=MID$(Z$,P,1):P=P+1: IF A$<>" " AND A$<>"" THEN 730

710 IF P>Z THEN GOSUB 800

720 GOTO 700

730 IF A$="]" THEN A$=" "

740 IF A$="#" THEN A$=CHR$(34)

750 IF A$="^" THEN A$=":"

760 IF P>Z THEN GOSUB 800

770 RETURN

780 '

790 REM -- SUBROUTINE TO READ NEXT LUMP OF DATA

800 READ Z$:Z=LEN(Z$):P=1

810 IF Z$="PAUSE" THEN FOR D=1 TO 20000:NEXT: GOTO 800

820 IF Z$="FINISH" THEN PRINT #1, CHR$(12)+RESET.CODE$: CLOSE #1:END

830 RETURN

840 '

850 REM -------------------------------------

860 REM * DATABASE1 - H.R.H. PRINCE CHARLES *

870 REM -------------------------------------

880 '

890 DATA "H.R.H. Prince Charles"

900 DATA 79G/79G/79G/79G

910 DATA /79G-25]2.2^2&^L2^2&3^2.

920 DATA /26G16@&36G-22]2.^9]&S&3S2&3^.

930 DATA /22G23@34G-20].^10&]3&^6Y2C&^.

...

4710 '

4720 REM -- EXPLANATION OF DATA --

4730 REM / MEANS NEWLINE

4740 REM - MEANS CONTINUATION LINE

4750 REM 29G MEANS PRINT 29 LETTER G'S.

4760 REM @ MEANS PRINT ONE @ CHARACTER.

4770 REM CHARACTERS : " AND 'SPACE'

4780 REM ARE REPRESENTED BY ^ # AND ]

4790 REM IN THE DATA STATEMENTS.

4800 REM ALL OTHER CHARACTERS ARE

4810 REM PRINTED OUT AS THEMSELVES.

The full code is available, along with documentation.

Like typewriters, dot matrix printers could carry out a carriage return without line feed. Today’s inkjet and laser printers cannot do that. I pose a challenge:

convert the program to a modern language (MATLAB or Python are natural choices) and modify it to render the images in some appropriate format.

References

- A. R. Neill. Bob Neill’s Book of Typewriter Art (With Special Computer Programme). The Weavers Press, 4 Weavers Cottages, Goudhurst, Kent, 1982, 176 pp. ISBN 0 946017 01 8.

- A. R. Neill. Bob Neill’s Second Book of Typewriter Art. The Weavers Press, 4 Weavers Cottages, Goudhurst, Kent, 1984. ISBN 0 946017 02 6.