I first met Hans in 1984 at the Gatlinburg meeting IX in Waterloo, Canada, at which time I was a PhD student. When I discussed my work on matrix square roots with him he recalled a 1966 paper by Culver “On the Existence and Uniqueness of the Real Logarithm of a Matrix”, of which I was unaware. By the time I returned to Manchester, after visiting Stanford for a few weeks, a copy of the paper was waiting for me, with an explanation of how the results of that paper could be adapted to analyze real square roots of a real matrix.

As chair of the 2002 Householder symposium XV in Peebles, Scotland, I was delighted to invite Hans to deliver the after-dinner speech. (The Gatlinburg meeting was renamed the Householder symposium in 1990, in honour of Alston Householder, who organized the early meetings.) Having Hans speak was particularly appropriate as he had studied at the nearby University of Edinburgh. I believe this was the last Householder Symposium that Hans attended.

I kept a copy of my introduction of Hans at the banquet. It seems appropriate to reproduce it here.

Ladies and gentlemen, our after-dinner speaker this evening is Hans Schneider, who is James Joseph Sylvester Emeritus Professor of Mathematics at the University of Wisconsin.

There’s an old definition that an intellectual is somebody who can hear the William Tell overture and not think of the Lone Ranger. I don’t think there are many people who can hear the term “linear algebra and its applications” and not think of Hans Schneider. After all, Hans has been Editor-in-Chief of the journal of that name since 1972, and developed it into a major mathematics journal. Hans was also instrumental in the foundation of the International Linear Algebra Society, of which he served as President from 1987 to 1996.

Some of you may be surprised to know that Hans has a strong connection with Scotland. He studied here and received his Ph.D. at Edinburgh University in 1952 under the famous Alexander Craig Aitken. I understand that Aitken gave him two words of advice: “Read Frobenius!”.

Well, it’s a real pleasure to introduce Hans and to ask him to speak on “The Debt Linear Algebra Owes Helmut Wielandt”.

The reference to Frobenius is apposite, given my original conversation with Hans since, as I have only recently discovered, Frobenius gave one of the earliest proofs of the existence of matrix square roots in 1896. That result, and much more about Frobenius’s wide range of contributions to mathematics is discussed in a 2013 book by Thomas Hawkins, The Mathematics of Frobenius in Context. A Journey Through 18th to 20th Century Mathematics (of which my copy has the rare error of having the odd pages on the left, rather than the right, of each two-page spread).

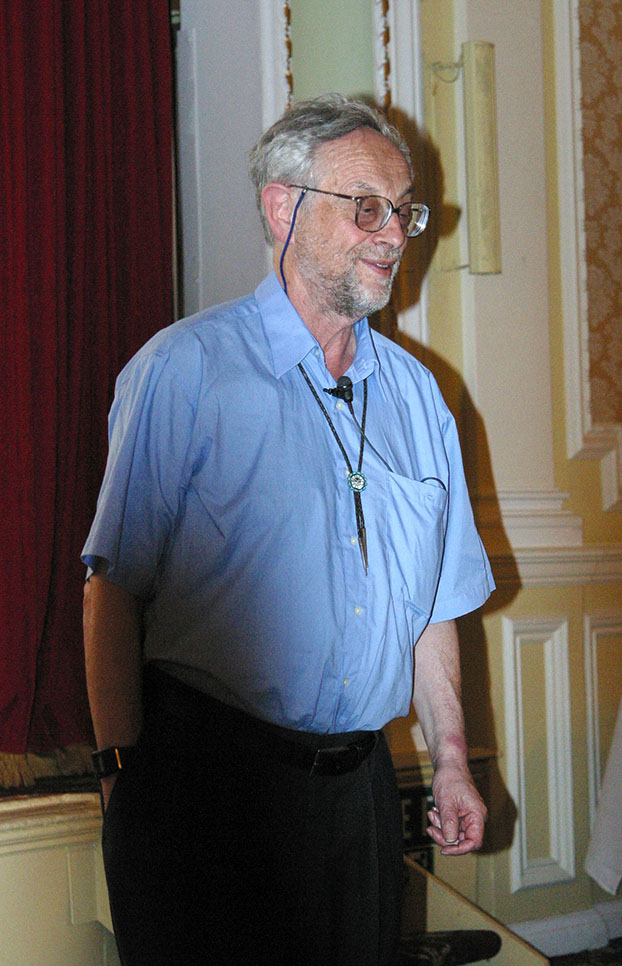

The photo below was taken during Hans’s after-dinner speech (more photos from the meeting are available in this gallery).

Links:

- Hans’s home page.

- Memorial page for Hans.