The MATLAB function sqrtm, for computing a square root of a matrix, first appeared in the 1980s. It was improved in MATLAB 5.3 (1999) and again in MATLAB 2015b. In this post I will explain how the recent changes have brought significant speed improvements.

Recall that every -by-

nonsingular matrix

has a square root: a matrix

such that

. In fact, it has at least two square roots,

, and possibly infinitely many. These two extremes occur when

has a single block in its Jordan form (two square roots) and when an eigenvalue appears in two or more blocks in the Jordan form (infinitely many square roots).

In practice, it is usually the principal square root that is wanted, which is the one whose eigenvalues lie in the right-half plane. This square root is unique if has no real negative eigenvalues. We make it unique in all cases by taking the square root of a negative number to be the one with nonnegative imaginary part.

The original sqrtm transformed to Schur form and then applied a recurrence of Parlett, designed for general matrix functions; in fact it simply called the MATLAB funm function of that time. This approach can be unstable when

has nearly repeated eigenvalues. I pointed out the instability in a 1999 report A New Sqrtm for MATLAB and provided a replacement for sqrtm that employs a recurrence derived specifically for the square root by Björck and Hammarling in 1983. The latter recurrence is perfectly stable. My function also provided an estimate of the condition number of the matrix square root.

The importance of sqrtm has grown over the years because logm (for the matrix logarithm) depends on it, as do codes for other matrix functions, for computing arbitrary powers of a matrix and inverse trigonometric and inverse hyperbolic functions.

For a triangular matrix , the cost of the recurrence for computing

is the same as the cost of computing

, namely

flops. But while the inverse of a triangular matrix is a level 3 BLAS operation, and so has been very efficiently implemented in libraries, the square root computation is not in the level 3 BLAS standard. As a result, my sqrtm implemented the Björck–Hammarling recurrence in M-code as a triply nested loop and was rather slow.

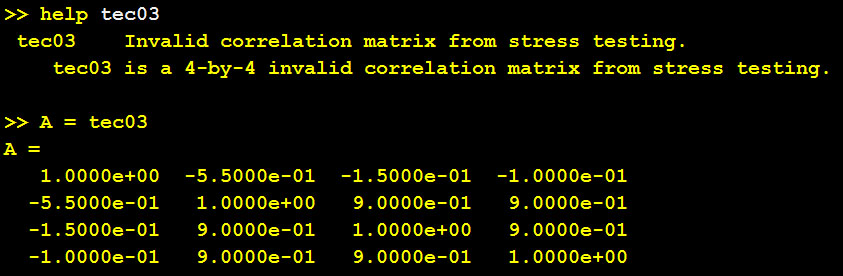

The new sqrtm introduced in MATLAB 2015b contains a new implementation of the Björck–Hammarling recurrence that, while still in M-code, is much faster. Here is a comparison of the underlying function sqrtm_tri (contained in toolbox/matlab/matfun/private/sqrtm_tri.m) with the relevant piece of code extracted from the old sqrtm. Shown are execution times in seconds for random triangular matrices an a quad-core Intel Core i7 processor.

| n | sqrtm_tri |

old sqrtm |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.0024 | 0.0008 |

| 100 | 0.0017 | 0.014 |

| 1000 | 0.45 | 3.12 |

For , the new code is slower. But for

we already have a factor 8 speedup, rising to a factor 69 for

. The slowdown for

is for a combination of two reasons: the new code is more general, as it supports the real Schur form, and it contains function calls that generate overheads for small

.

How does sqrtm_tri work? It uses a recursive partitioning technique. It writes

and notes that

where . In this way the task of computing the square root of

is reduced to the tasks of recursively computing the square roots of the smaller matrices

and

and then solving the Sylvester equation for

. The Sylvester equation is solved using an LAPACK routine, for efficiency. If you’d like to take a look at the code, type

edit private/sqrtm_tri at the MATLAB prompt. For more on this recursive scheme for computing square roots of triangular matrices see Blocked Schur Algorithms for Computing the Matrix Square Root (2013) by Deadman, Higham and Ralha.

The sqrtm in MATLAB 2015b includes two further refinements.

- For real matrices it uses the real Schur form, which means that all computations are carried out in real arithmetic, giving a speed advantage and ensuring that the result will not be contaminated by imaginary parts at the roundoff level.

- It estimates the 1-norm condition number of the matrix square root instead of the 2-norm condition number, so exploits the normest1 function.

Finally, I note that the product of two triangular matrices is also not a level-3 BLAS routine, yet again it is needed in matrix function codes. A proposal for it to be included in the Intel Math Kernel Library was made recently by Peter Kandolf, and I strongly support the proposal.

I learned about Anderson acceleration in the minisymposium

I learned about Anderson acceleration in the minisymposium